Part3:To Another Country

Japanese Photographers See the World

Sep. 29—Nov. 23, 2009

- Sep. 29—Nov. 23, 2009

- Closed Monday (Tuesday if Monday is a national holiday)

- Admission:Adults ¥500(400)/College Students ¥400(320)/High School and Junior High School Students, Over 65 ¥250(200)

Part 1 To Strange Lands—The Pictorial Landscape

Fukuhara Shinzo and Yasumoto Koyo photographed landscapes encountered in their travels in the style known as Pictorialism, an approach that focused on the beauty of the subject matter, tonality, and composition, bringing photography into the realm of fine art. After studying in the United States, Fukuhara traveled in Britain, Germany, and Italy, before arriving in Paris, in the spring of 1913. There the camera he had ordered in Britain, a Tropical Soho, arrived and, camera in hand, he set out regularly for the banks of the Seine. The resulting photographs were published in 1922 as Paris and the Seine. After returning to Japan, Fukuhara would advocate his theory of photography in the book Light with Its Harmony and become a driving force in Japanese photographic circles. His Paris and the Seine, however, follows the trend to Pictorialism that was widespread in Europe and the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The landscapes that Yasumoto Koyo captured during his travels were also brimming with his intensely lyrical Pictorialism. His are painterly landscapes with a touch of nostalgia, even homesickness, even though the scenes he photographed were in alien lands. Yasumoto traveled around the world in 1931 to 1932 to observe what was happening in the world of photography in Europe and America. The images from strange lands he photographed during that trip differ greatly from Fukuhara’s, in whose work backgrounds and figures are rendered abstractly or subjects afloat among hazy silhouettes. While Yasumoto worked in soft focus, he retained the fine details of the landscape, creating a fairy-tale-like visual fantasy.

Part 2. The Gaze of the Stranger

To photographers responsible for carrying out professional assignments, the meaning of “travel” is very different than it is for most people. To these photographers, the goal of travel must, in many cases, be photography itself. Natori Yonosuke’s words bring to mind the ultimate in travel, freed from assigned tasks, and the hardships he underwent as a professional photographer: “Work. Work. Work. It haunts me constantly on my travels. On my next trip, I’d like to forget my camera and all that and just go. How I wish I could.” Such professionals were obsessed with photography as a commitment, an obligation, and were not free from the spell of photography even when traveling. Their sense of urgency, of needing to capture something in their limited time in another country, drove them to immerse themselves in the visual world of photography. The experience of being in a place different from that of the everyday is, however, an opportunity to experience new sensations and perceptions that one is not conscious of while embedded in everyday spaces. Their experiences in strange lands also reveal about new aspects of these photographers to use.

Part 3. In Quest of Self

Travel is a magical device that transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary. Landscapes routinely overlooked because they are too familiar are bathed in fresh color when travel sharpens perceptions and awareness. Today, the traveler and the camera are a set: the acts of traveling and of taking pictures, actively freezing and remembering visual images experienced in an extraordinary space, have, almost unconsciously, become a perfect pair. Through that act of photography, or as its result, the afterimages of travel so created--images frozen as photographs--can be contemplated at leisure. The experience of a moment, brought by chance, begins to acquire clear contours as images reproduced as memory and reality overlap. Photographers who had already established their own styles in Japan traveled overseas in search of the next level. Theirs were journeys in search of their own raisons d’être.

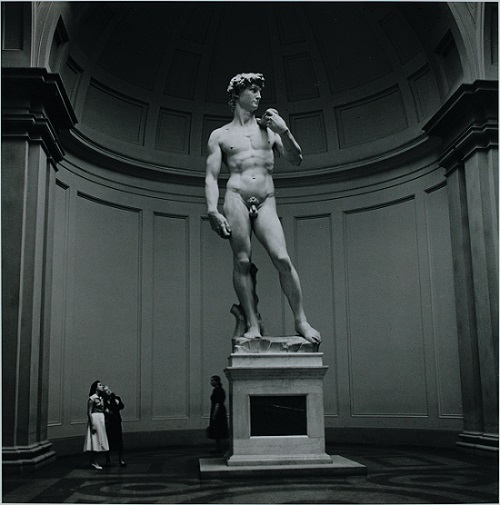

Part 4. Travel as Witness to History

Photographers who travel through history, visiting historic sites create intersections between the present and memories of the past, weaving together a world of historic significance. In their work we glimpse the irrepressible lust for pure travel and the wish to create recollections of what only these eyes have seen of the world--motives that drive the photographer. In strange lands, one rediscovers realities stirred up on one’s travels. Yet, at the same time, everyday life keeps proceeding normally there, even if one is oceans away from home. Photographers, standing at the crossroads of the ordinary and the extraordinary, try to freeze for all eternity the landscapes that have crossed and stimulated their retinas. The greatest benefit of travel is probably that one can see and experience the world stretching out before one’s eyes, for oneself, not at second hand, as borrowed reality, by proceeding directly there for oneself. The photographer as traveler directly encounters the living, breathing world, for which a photograph is never a replacement, and a momentary scene that cannot be repeated a second time, yet shows it to us, exciting our love of strange lands. That is a true sharing of memories, exchanged between photographers and ourselves.

NARAHARA Ikko, Venezia 'Where Time has Stopped 1964

MINATO Chihiro, Le Lote Basque, Biarritz "O Brico Allantico" 1986

![チラシ1[pdf]](http://topmuseum.jp/upload/4/87/thums/2009_008_part3.png)

![出品作品リスト1[pdf]](http://topmuseum.jp/upload/4/87/thums/2009_part3_list.png)