Part 1 The Star-Spangled Banner

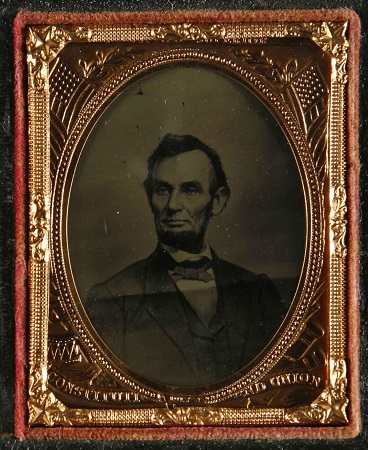

Mathew Brady’s Studio, Title Unknown (Portrait of Abraham Lincoln), c.1860

Visions of America

Part 1 The Star-Spangled Banner

Jul. 5—Aug. 24, 2008

- Jul. 5—Aug. 24, 2008

- Closed Monday(if Monday is a national holiday or a substitute holiday, it is the next day) ※Open is Jul.22

- Admission:Adults ¥500/College Students ¥400/High School and Junior High School Students,Over 65 ¥250

The United States has been a world leader in photography from its pioneering days through the present, but its influence was especially great during the twentieth century. That nation has also been crucially important as both a creative setting and a subject for not only American but also European and Asian photographers.

Visions of America, an exhibition in three parts from the collection of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, introduces many types and styles of photography from the United States, from nineteenth-century daguerreotypes to contemporary work. Selected from the 24,000 photographs in the museum's collection, these works are being exhibited by period. As the series unfolds, the Visions of America exhibition presents not only a view of the history of the United States since its foundation but also the multi-layered nature of its culture, with its complex relationships between the global and the local.

Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage, 1907

Lewis Wickes Hine, Climbing into America, Ellis Island, 1908

1. The Daguerreotype Arrives in America

On August 19, 1839, the invention of the Daguerreotype, the world’s first photographic process, was announced at a meeting of the French Academy of Science. Barely a month later, Samuel Morse, famed as the inventor of Morse Code, took a portrait photograph of his wife and daughter in New York, using what would now be an unthinkably long 20-minute exposure. The following year, 1840, the Daguerreian Parlor, the world’s first photography studio, opened in New York. That event heralded the dissemination of the photographic process throughout the country, with Boston and Philadelphia particularly important centers of activity. In America, it is no overstatement to say, photography began with the portrait.

2. A War Photographed, a Myth Invented

The American Civil War, which left more than 610,000 dead, was the beginning of wartime news coverage through photography. Earlier wartime photographs were used in order to document and report actions within the government or military. In the Civil War, photography expanded far beyond that limited role. Matthew B. Brady organized a team of 25 photographers, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, set up darkrooms in horse-drawn wagons, and dramatically photographed the Union or Northern army, in and out of battle. Brady then printed and sold the images as photograph albums. Most of the photographic record of the Civil War is from the point of view of the winners, the North. Victory in that war, in which in the call to free the slaves was a rallying cry, was transformed into myth, an historical event symbolizing America, the “land of the free.”

3. Westward, Ho!

The frontier was defined as an area with a population density of two to six people per square mile (2.56 square kilometers). The photographic work of Timothy O’ Sullivan, Carleton Watkins, William Henry Jackson, and other photographers, captured the expansion of the frontier outline westward. This body of work is what became known as the golden age of landscape photography in the United States. Many of their images have the feel of beautiful landscape photographs. But these photographs were produced for a practical purpose, to analyze the natural landscape of the West that the photographers were engaged in studying.

4. The Man Who Stopped Motion

The question: Does a galloping horse ever have all four hooves off the ground when its legs are at full extension? In 1872, Leland Stanford was engaged in a wager with another man (also involved in horse racing) over this question. That same year, Stanford (a former governor of California) hired the photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) to conduct experiments to settle the issue. Muybridge designed a huge photographic device and conducted six years of experiments that ended in success. His work demonstrated that a galloping horse lifted all four hooves off the ground only when its legs were tucked underneath its body, not at full extension. The “Horse in Motion” experiments led Muybridge to his life’s work, photographically breaking down human and animal motion to a thousandth of a second. His studies gave birth to the snap shot and to snap shots in sequence, the starting point for the motion picture.

5. Social Betterment

After the Civil War, accelerating waves of industrialization and urbanization struck the United States and, in a capitalist context, gave rise to a host of social problems. Jacob A. Riis trained his camera on the slums of New York; Lewis W. Hine photographed the status of immigrants and child laborers. Their work was more than a faithful record of social realities; it was consistently informed by their determination to reform those cruel realities. Photography, as a means to spur society into action, showed its power in a place called America.

6. Photography as an American Art

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the idea of photography as an art form took off throughout the world. Pictorialism, photography that imitated painting, was the first style of art photography to emerge. Alfred Steiglitz, later called the “father of modern photography,” turned away from that approach, organized the Photo-Secession in 1902, and began a search for art photography uniquely American, rejecting European models. The work Steiglitz published in Camera Work, the journal of the Photo-Secession, eloquently demonstrated that a photographic style rooted in the cultural landscape of America was ready to lead the world.

![チラシ1[pdf]](http://topmuseum.jp/upload/4/380/thums/2008_007_b.png)