An Interview with exonemo

The beginnings of internet art

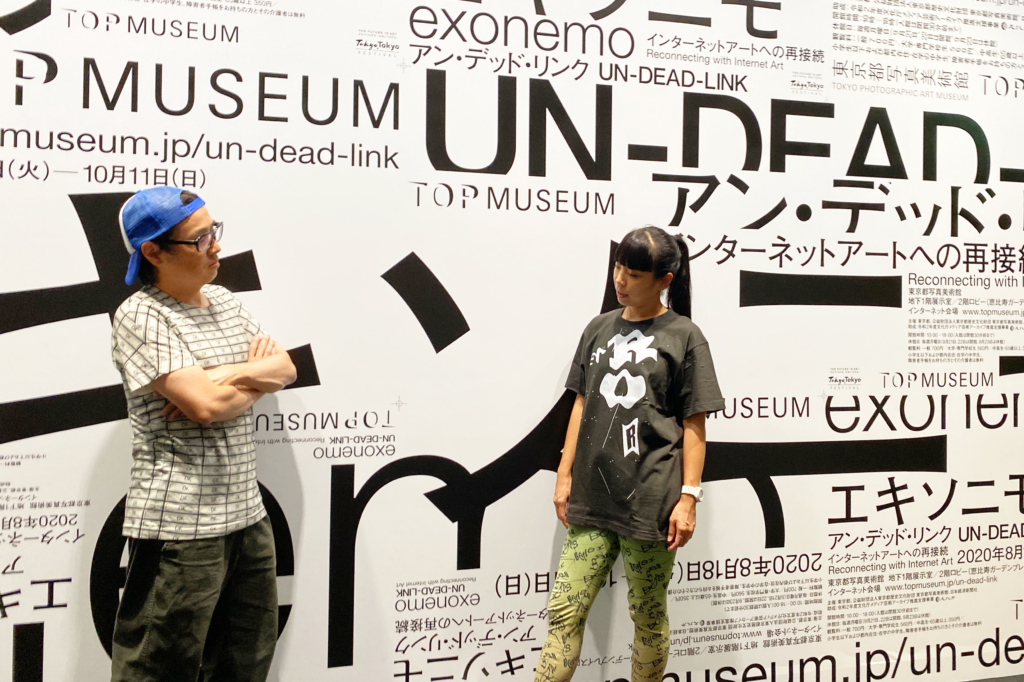

It was partly the ongoing coronavirus crisis that inspired the idea for this exhibition’s format, which links artwork at the museum to an online venue in real time. But it turned out to be a fitting approach for this retrospective of exonemo’s 24-year career to date. You’ve given this exhibition the subtitle “Reconnecting with Internet Art” – first of all, what is “internet art” to you two?

Sembo: Well, first of all, I think we belong to the first generation of artists who started out our careers online. For young people these days, there’s probably nothing new at all about using the internet as their first platform, but very few people did that back then. The internet was only just beginning to become widely used, and although there were people who would extend their offline activities to the online world, hardly anyone made their start online. So I think that there’s a huge gulf between how today’s net artists see the internet and how we see it.

As our career went on, we came to exhibit more and more in real-world venues, gradually drifting away from net art. In recent years in particular, our focus has been shifting towards materials and spaces. But then came this coronavirus pandemic. Real-world spaces got temporarily shut down, causing a spike in an internet addiction of sorts, and this has given a whole new sense of reality to net art. All this made us think again about what we could do using the internet, which was where we’d started all those years ago. To a large extent, I guess that motivated the sudden change in direction that this exhibition has taken.

When you started your online activities, there were already net artists overseas, like Jodi and Ubermorgen. Was the whole internet art movement something you were aware of?

Akaiwa: For the first few years, maybe from 1996 to 1999, we were making our work without knowing about the internet art movement. To us, it was just something new that we might be able to do using the internet. We didn’t know what it was that we were making, we didn’t even consider them artworks as such – it was just a playground we were building for ourselves, as it were. Then, around 1999, we were introduced to Jodi for the first time, and learned that there were others doing the kind of things we were doing. That was when we started being aware of the whole idea of “internet art.” We’d never really situated our output in any genre – they might have been artworks, they might have been games – we were really just making things and putting them on the internet.

Was there a part of you that wanted to set yourselves apart from art – to do things differently from the art world?

Akaiwa: There was a sense of that, sure. We really wanted to do something interesting, but we didn’t necessarily want that to be art. When you express yourself using traditional media and materials like paper, it’s hard to make changes afterwards. So it can get quite tense, because you have to set a specific goal and stick to it. But with the internet, you can keep on updating that expression, and even use programs that continually generate something new. From time to time, we’d also receive direct messages about our work from someone overseas, totally out of the blue – we loved that fresh sense of tempo and distance that the internet offered. It was all so exciting that we felt we had to do it. It was just that we didn’t think of it as art, at least to begin with.

Sembo: The first work, KAO (1996), was sort of like fukuwarai [a children’s game like “Pin the Tail on the Donkey,” in which blindfolded participants try to place cutouts of facial features onto a drawing of a face]. Visitors to the website would pick and choose some eyes, a nose and a mouth to compose a face, then click “Send.” That face would then be combined with another face on the server to produce a new face, a “child” that takes after the two parent faces. This would then be combined with the next face that someone inputs, creating yet another child, and so on. It was a simple system. We were very young when we made that – and a bit foolish, a bit cocky. We’d just graduated from art college, where a lot of students were still using traditional media like painting and sculpture, and there was a part of us that looked down on them a bit. We were like, “Why so old-fashioned?” We were also skeptical and a little dismissive about the idea of human beings trying to create something through conscious intent. KAO alters your chosen face the moment you hit “Send,” synthesizing it with the previous face, and spawning a new offspring. There was definitely an “in-your-face” element about that, as if we were going, “Look, we’re destroying what you created.” Looking back now, it all seems so young, but at the time we certainly had a desire to defy all those sorts of conventions.

The birth of exonemo

Exonemo appeared on the scene around 1996, but the two of you didn’t really show your faces at the start. You struck me as these very “punk” people who’d emerged out of the street culture. The whole idea of net art was appealing for sure, but there was such energy about these anonymous activities you were rolling out. You seemed to be more in touch with the music and alternative culture scenes than with the art scene.

Akaiwa: You’re right, I guess we weren’t really part of the art world. After all, we were doing it all online, we rarely showed our faces, and no-one knew who we really were.

Sembo: We’d also intentionally picked a name that would obscure who we were, or even what country we were from.

There are many art collectives, but artist duos are fewer and farther between. Are they more common in net art?

Akaiwa: They are. Take Jodi for example – even though it’s a woman’s name, we’d imagined for some reason that it’d be an overweight, nerdy type… [laughs] But then we met them, and it turned out to be a couple doing it, a man and a woman. It totally caught us by surprise. 0100101110101101.org and Ubermorgen were couples too, and a number of others that we’ve met. We worked as a pair because we only had one computer between us. We were sharing one computer, one e-mail address, everything. Now, all these artists have a computer each or more, but back in those days, I imagine that a lot of them were just sharing one computer at home. I think that’s why there were so many couples in the early days of internet art. It’s just my own theory, but I’m pretty sure there’s some truth in it. [laughs]

Another feature of these artist groups is their distinctive names – like “Jodi” and “exonemo” – which tend to be poetic and evocative. Can you tell us about the name “exonemo”?

Akaiwa: Well, anonymity is a key element of the internet, so artists often go for names that allow their personal identities to take a back seat. That’s what we did too.

Sembo: Zero-one [0100101110101101.org] apparently chose its name by rolling a die. That comes from a wish to remove the individual and his conscious decisions from the equation. It’s related to the open-source movement in that sense. In the early days of the internet, there seemed to be this ideal – fantasy, perhaps – that it wasn’t individuals that would change society, but the anonymous many.

Akaiwa: The word “exonemo” has no meaning either. When you’re deciding on a name for a group or a company, you usually try to think of something that encapsulates your vision, your concept. So we came up with all sorts of ideas, but none of them clicked. Something wasn’t right, so we kept on thinking and thinking until our brains were fried – then this random word “exonemo” just happened to pop out of my mouth. And we were like, “Oh, that’s quite good!” This was a totally new word that only existed as a sound, so we had to then work out how to write it. It took a while for the name to sink in, to really feel like our name – at the start, it felt strange being called by it. But it eventually grew on us, and grew in meaning too. That was an interesting change. Having a made-up word for a name also turned out to have practical advantages online – for example, when people searched our name, the only results that came up were pages related to us.

Did having a name make you start identifying more strongly as artists?

Sembo: That was a bit of a dilemma for us. At the start, we saw individual agency as a negative, which is why many of our works from that period were “tools”: KAO went about breaking something that had been made, DISCODER (1999)messed up websites’ source codes, and FragMental Storm (2000/ 2002/ 2007/ 2009) mixed together images from different web pages. Back then, our notion of creativity involved using randomness to dismantle human intention. In that sense, it was a methodology that sought to play down our own individuality. But as our career continued, this policy itself started becoming our public identity. Concealing ourselves also posed difficulties when it came to trying to expand our activities. So our stance gradually changed.

The future of the real and the online

You also began to create more material works, like all the installations you made in the 2000s, which explored new territories and addressed wider social issues. Do you consider your internet art, then, as just an early phase of your career, or as an ongoing enterprise that you’re still engaging with today?

Sembo: I think that the so-called “net.art” of the early days and today’s net art are totally different. I see the former as an experimental phase when new frontiers were being discovered, which artists would then explore by creating art out of them. But then the internet became all-present, and accessible to everyone too. So people could use it to put out a rich variety of artistic expressions, and they also gained the web skills with which to make smooth flash animations, sync sound with them, and so on. They could even utilize all the artistic methods of the past in their toolbox. So then, it was no longer about things you can only do online, but things you can also do online. Like how movies screening at regular cinemas can now be watched on your browser too. So today, it’s less about the particular nature of the online medium: the internet has just become a vehicle, a vessel. If you look at today’s net artists, many of them just do things like present their CG work online. We’re seeing more and more stuff that isn’t predicated on the internet, and there’s very little left of the “pure” net art of the early era.

Akaiwa: Back in the ’90s, in the earliest days of internet art, the act of going online was still something very special – you were basically entering into another world. That’s why much of net art from back then was set up as an experience in that other world, a world detached from our reality. But since around 2000 or so, as the boundary between the real and digital worlds began to blur, we started seeing more works that straddled, or moved fluidly between, those two worlds. So the propagation and evolution of the internet has really changed the face of net art.

Sembo: The “Post-Internet” movement also came along later. As I see it, the idea of that is to try to import into the physical world those sensations and feelings that can only be found online. In that sense, it’s a countercurrent of sorts.

It was with all this in mind that we made Realm (2020), one of our new works. It’s an attempt to return to the early days of net art – to create spaces and tactile sensations that can’t exist outside of the web.

Akaiwa: Whether we’re conscious of it or not, we can never be totally free of how we first perceived and experienced the internet in the mid-90s, when we began using it. I sometimes think about how that sense has stayed with us all along, even as we create our work in the digital and analog worlds. Though our ventures like Internet Yami-Ichi (2012-)and IDPW explored novel ways to approach the digital and the real, they were very much grounded in the sensibility of people who got acquainted with the internet as adults. Today’s young children, on the other hand, have been exposed to the internet since they were born, so they use it in a completely different way. Zoom-nomi [drinking together over the Zoom video chat app] has become popular in the current coronavirus crisis, but that too is a forced attempt to make a real-world activity work online as a way to communicate. But for children today, what happens in an online game is very much a part of their reality. For example, our daughter often uploads photos of nature on Instagram. We go for a walk every day in a big cemetery nearby that has splendid nature, and she likes to take photos of the trees and flowers there. She also loves the game Minecraft, which involves building structures and earthworks in this virtual natural terrain. And if you look on her Instagram, there’s a total mix of nature from the real world and nature from the Minecraft world, and they seem to bear a relation to each other. She’s treating the online and offline natural worlds in the same way. Her generation seems to have no sense of “this side” and “that side”; the boundary is very fluid for them.

I guess the world is still built and run by people who were introduced to the internet some time into their lives, so it’s all still in their language. But when today’s children become the ones building the world, it’s going to be a totally different landscape – is that the sort of thing you’re saying?

Akaiwa: Yes, when I watch those kids, I become more aware that I still haven’t shed that idea of “this world” and “that world” – that my own attitude to our art is still informed by the sensibilities of early internet art. But if we stick with that, maybe that will eventually become our distinctive style. To younger people, it’ll be like, “Why are they even doing that?” [laughs]

2011 Tohoku earthquake and moving to New York

You’ve stated that you set up Internet Yami-Ichi after beginning to feel stifled in the online world. Then a little later in 2015, you made the move to New York. What motivated you to relocate?

Akaiwa: That decision can be traced back to the earthquake [the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami] – that was the biggest factor. We were in Tokyo when it struck, and we decided to go to my family home down in Fukuoka because we had a young daughter and everything. We can do our activities anywhere, so we left Tokyo to base ourselves somewhere else for a change. While in Fukuoka, we contacted friends all over Japan and began holding sporadic experimental events, putting together a group around the theme of internet and reality. One of those events was World Wide Beer Garden (2012), which was like the Zoom-nomi. It was an online beer garden that people could participate in from different locations, drinking together over video chat. Internet Yami-Ichi was another project that came out of that. We did Yami-Ichi twice in Japan, then started thinking where we could do it next. We wanted to find out if it was something that only worked in Japan, or if it would be received well overseas too. Then we happened to get approached about doing Yami-Ichi at Transmediale 2014, so we took it abroad for the first time. Yami-ichiss had an open platform policy, and anyone was welcome to recreate it – and so it began spreading on its own. Until then, we’d never once thought of moving overseas, because we loved Tokyo and found it so exciting. But as we continued our activities in Fukuoka while observing the rest of Japan, Tokyo began to seem very local. We imagined that Japan too would seem local if we saw it from outside, and started wanting to leave Japan, at least for a while. That’s how we decided to go to New York.

Sembo: There were two reasons for the move, one of which was the earthquake. Before then, we were very attached to Tokyo. Even when we went to exhibit overseas, we just thought Tokyo was far more exciting. But all that evaporated immediately after that disaster. Our daughter was just under two years old then, and the experience made us realize that family was what we valued the most. If the earth was going to shake, it was better to be able to move freely as a whole family. And just like that, we stopped being particular about where we live.

The other factor was social media, which were becoming prevalent around the same time. Twitter was getting popular, Ustream became a thing, and more and more internet-based creative types were appearing on the scene. I was very much a part of that world then, so I was involved in that boom. But the dialogue was all in Japanese, and this slowly narrowed my perspective of the world at large. And before we knew it, our activities were becoming increasingly limited to Japan, partly because it wasn’t as easy to go overseas with a young child and all. Then, just as our activities were getting totally domestic, we suddenly remembered what the internet was like in the early days, about its open atmosphere. We were just putting our works on our website, but we received a fair amount of enthusiastic feedback from people overseas that we didn’t know. But that wasn’t really happening so much anymore, and it felt like everything was becoming very closed. We really wanted to break out of that.

I see. So the original net art boom from back in your early days had subsided by the 2000s?

Sembo: I think net art reached its peak around the year 2000 – I even read an article somewhere titled “net.art is dead.” It became too commonplace and lost its edge. Then came the age of social media. Our own activities got increasingly domestic, it was all becoming more rapid and more condensed, shrinking in scale and scope. We wanted to escape that, and it was this feeling that ultimately led us here to New York.

Akaiwa: I agree, it did feel like everything was becoming more closed. But that tends to happen in every country, and the US is no exception.

Did your start to see Tokyo differently too?

Sembo: Living in Fukuoka after the earthquake, I discovered that people down there knew nothing about what I’d referred to as subcultures back in Tokyo. I’d always assumed that these were Japanese subcultures, but I realized then that they were Tokyo subcultures. The only thing I could talk about with people in Fukuoka was mainstream culture – TV, celebrities, that sort of thing. It really struck me how these subcultures were much smaller than I could have imagined.

Akaiwa: We realized how hard it is to see these things from the inside. That scared us because the same thing could apply to Japan and the rest of the world. So we decided to try living somewhere else while we still had the stamina, because we probably wouldn’t have that stamina in ten years’ time. So it was a now-or-never situation. [laughs]

Sembo: Our daughter had just finished kindergarten too, so it was the perfect timing. We decided we should start with the place that would require the most stamina. Though we had no particular feelings about New York itself.

Akaiwa: No, I wasn’t even a fan of America, really.

New York didn’t seem to have a big internet art community either, so your choice of New York over a European city like Berlin came as a surprise.

Sembo: We weren’t after somewhere where we’d have it easy. We did want to go to an English-speaking country – or at least a city where we could get by in English – because we wanted to pick up the language. Berlin and Amsterdam were options too, but we felt we might get too comfortable in those cities and get nowhere as a result. We weren’t looking for places that would be welcoming for artists like us.

Akaiwa: Or where internet art was in vogue.

Sembo: We only picked New York because it was an English-speaking city that would be a real challenge for us – and a rewarding one at that.

I myself tend to think about things in terms of “before” and “after” the earthquake too. So it had a huge impact on you two, then?

Akaiwa: Yes, it was a major turning point.

Sembo: Something changed then, didn’t it? In the wake of the earthquake, many artists responded to the whole situation through their art, through charity activities, and so on, and many spoke up against nuclear energy. But that didn’t feel very real to us somehow. I think that kind of thing will take shape over time and emerge naturally. As far as my own experience goes, it usually takes around two years for some event to really sink into my body and find its way into my work. And I don’t see anything wrong with waiting for that to happen. With the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement too, there’ll be artists who respond to it immediately by creating artwork, and many others will participate in protests, make statements, and so on. But if you let your experience and your awareness of issues ferment within you, then it’s going to affect your work in one way or another. And I’m not sure if acting immediately is what it really means to react. So I continue working on my art, believing that consciously driving myself to take action isn’t the only answer – that it will all become ingrained in me over time and ultimately come out in my work. That’s another way to react.

Art in New York and beyond

Exonemo’s works seem to be changing too. The Kiss (2019), for example, is visually very pop and appears relatively straightforward, though that impression can be a little deceptive. But you do seem to be making more works that instantly catch the eye.

Akaiwa: That’s really to do with the environment. In a place as diverse as New York, you can’t get your point across if you try to be subtle. In Japan, artists tend to aim for really subtle nuances. So subtle that even if a work misses the mark, it’s hard to tell sometimes.

Sembo: We ourselves used to try to throw curveballs sometimes when we were in Japan. But now, it’s like we can only throw straight balls, right down the middle.

Akaiwa: A down-the-middle straight ball can also come unexpected. What we Asians, what we Japanese people think of as a straight ball might seem like a curveball to people elsewhere. Curveballs might have a localized appeal within a small community, but all that gets totally lost outside. I think that’s where being pop or being direct comes in.

Sembo: Like with The Kiss – we’d have never used that word had we been in Japan. Same with I randomly love you / hate you (2018), we would have felt too embarrassed to use direct words like “love” and “hate” in Japan. But over here, you need to be that direct if you want to get the idea across.

Akaiwa: The viewers are diverse, so they react in totally different ways. If you don’t express yourself directly, you can’t elicit those diverse reactions.

What were the first works you made in New York?

Sembo: We made Body Paint (2014)in Japan, but HEAVY BODY PAINT (2016)was done in New York. Then there’s Kiss, or Dual Monitors (2017), and a few others like Feed (2016), the one with the screen eating.

Are you two conscious of changes in your work too?

Sembo: I don’t feel there’s anything fundamentally different. We’re expressing ourselves more directly, but that’s not a conscious decision. It just became that way naturally – inevitably, I might say. We don’t really try to consciously do things one way or the other, so to us, it doesn’t feel like we’re doing anything that differently.

Japan has a pretty well-connected community of artists – especially with places like ICC [NTT InterCommunication Center] and YCAM [Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media] – and it used to be mainly people from that general media art scene that seemed to dig our art.But over here, there has been totally new types of people recently, who seem to respond to our art in different ways. We’re also exhibiting more frequently in commercial galleries, so that’s caused a change in the people who come and see our exhibitions.

Is that the case in Japan too?

Sembo: Yes, that happened with the MAKI Gallery exhibition and Aichi Triennale too. Most of our viewers before were from that narrow community, but we don’t really hear from them at all these days – now we’re getting responses from all these new people we don’t know. It used to be the case that if we googled “exonemo,” we’d mostly find responses from people in the community, people in the know. But now there’s a totally new crowd, posting about how they’re looking forward to our exhibition, and so on.

Akaiwa: I guess the experiences and sensations that our art addresses have become very widespread. It was something we could only share with relatively tech-savvy people before, but now it’s becoming pervasive.

Sembo: Everyone uses the internet now, so the average level of digital literacy is higher too.

Akaiwa: In terms of UN-DEAD-LINK (2008), it’ll be exciting to see how that higher digital literacy and this whole coronavirus situation will affect people’s response to our internet art.

UN-DEAD-LINK and UN-DEAD-LINK 2020

So could you tell us a little about the work UN-DEAD-LINK, and why you’ve chosen this time of crisis to present an updated version of it?

Sembo: The original version was for an exhibition we did in 2008 at a Swiss gallery called plug.in. The work had a lot in common with an earlier work, Object B (2006), which also linked the real world to a 3-D game world. So in UN-DEAD-LINK, we set up a grand piano on the gallery’s first floor, along with various objects and electrical appliances like radios, lamps, a shredder, and so on, which turn on and off at seemingly random times. Various keys on the piano are playing scattered notes, and you have these radios going off at the same time – the whole space is an ensemble that emits all sorts of sounds. That alone might seem like a normal sound installation, but when you go down the spiral stairway to the basement, there’s a game showing on a screen in a dark room. The game involves 30 to 40 characters moving around automatically and killing each other, and when they die on-screen, that’s when the objects on the upper floor move. The characters are each linked to a particular key on the piano – but it’s only afterwards that the viewers become aware of this mechanism in which each character’s death sets in motion the actions on the floor above. There’s also a red button in the middle of the basement, and when you press it, everybody dies – and you hear all those notes go off at once on the piano above. So that’s the concept: a structure in which deaths in the in-game world have repercussions on the real world, thereby connecting the two spaces.

The work was inspired by an incident that happened some time ago. I can’t remember when exactly, but the two of us happened to be walking around in Kichijoji during the daytime when there was a sudden blackout. First the convenience store went dark, then we looked around and it was actually the entire town. We found out later that one of the Self-Defense Forces’ jets had crashed into a high-voltage line, causing a power failure in parts of Tokyo. That made us think: the jet crashed, the people on it died, and we ended up physically experiencing the moment they died. We were really shocked, bewildered even, by the fact that the moment of their death was experienced by people in tens of thousands of households. The Iraq War started a few years later, and we’d see reports about it all the time on the news. But on TV, all you’d learn is that this many thousands of militia fighters died in this or that air raid – it was just a series of numbers. All these experiences connected in our minds. Death is usually a very personal event – my father passed away in 2006, and it’s a devastating experience to lose someone close to you. But when deaths happening far away are reduced to mere numbers, and you hear about them in their tens, hundreds, and thousands, the reality of it just doesn’t register. That discrepancy bothered us, so we tried to capture that by having physical things in the real world react to deaths occurring inside the game world. Right now, there’s a similar thing happening again with the coronavirus. You have this constant stream of numbers – like how many people have died, or how many dozens have tested positive that day. But especially under lockdown, it’s hard to get your head around the fact that so many are dying. So it was these similar circumstances that suddenly got us thinking about UN-DEAD-LINK again, and we decided to create an updated version of it. It ultimately became the title of the whole exhibition. To explain the word “UN-DEAD-LINK,” a “dead link” is what you call links on the internet that no longer work. But these ones are “undead,” like zombies that have been brought back to life. Well, this is an exhibition that resurrects old works of internet art, and we’re also resurrecting and exhibiting this installation that can’t be seen any more. So we thought it’d be a fitting title.

exonemo expands its scope

Although exonemo’s works themselves have the power to stir emotions, there’s a certain coolness about the words and phrases you use in your titles. Is this a conscious choice? Is there a characteristic that the titles share?

Sembo: Many of the early works have titles that sound like tools, like DISCODER. We did note at one point that they’re like names of computer software.

Akaiwa: DISCODER is the only one that I can think of, but I do recall wanting to avoid titles like that, which just describe what happens when the work is set in motion.

Named after phenomena, physical objects and so on? The internet isn’t an object, but your work often transforms things from the online world into physical objects. I also get the impression that coming up with titles for your installations is an integral part of your activities.

Sembo: Right, yes. Body Paint (2014), for example, went through various titles. It was originally part of our installation titled God, Human, Bot(2014), which we’d made for the Grand Kojiki Exhibition.

Akaiwa: Then afterwards, when the work was removed from that context, the title didn’t feel right.

Sembo: I think we called it PHOTOPLASM after that, but scrapped that too. Then we were showing the work at some exhibition, and that gave us a chance to look at the work objectively. And we decided that a direct title like Body Paint would be more interesting. We’d originally come up with the idea for the work by saying that contemporary body painting would probably go further than to paint the body. So the final title was a kind of return to the work’s origins.

Akaiwa: It’s a question of whether or not the title itself contains a statement.

Like you find in many conceptual artists’ works. Your work does seem to share that element with conceptual art.

Sembo: True, like Duchamp’s Fountain. Maybe that’sa part of our aim – to use the title to cast the work in a different light, to inject a certain awareness.

I think that categorizing exonemo under “media art” would be overlooking these aspects of your work’s appeal. In fact, your work often seems to make more sense within the larger context of art history.

Sembo: Yes, I think our work would seem pretty dull if you only looked at it from a media art perspective.

Is your attitude to media art something that developed over the 24 years of your career?

Sembo: I’m not sure. Even before we started out, we didn’t really like media art. [laughs]

Akaiwa: We’ve rarely referred to ourselves as media artists – it’s just what people have tended to label us. But if people see us that way, we’re not ones to argue.

Sembo: Since we started exhibiting at very specialized festivals like Ars Electronica, it’s been happening more often that we see works of media art and feel unconvinced. [laughs] Sure, there are some exciting, meaningful works, but they give off little sense of their creators’ style or personality.

Akaiwa: I’ve no interest in those works that are like, “Look at us use this technology for a work of media art!”

Sembo: On a related note, I’ve been told that engineering students tend not to get anything out of a Jackson Pollock painting. And apparently, the reason it doesn’t register with them is that it has zero reproducibility. To them, it’s only by being reproducible that it becomes useful to society.

Akaiwa: Isn’t that a denial of art – an anti-art stance? Maybe it’s that they want to rise above the traditional conceptions of art.

Sembo: I get that impression from media art in general. Like it’s trying to say that everyone can use that same technology to create the same effect.

Akaiwa: That very premise is a rejection of previous ideas about art.

Sembo: Rather than present the artwork as the creation of a specific individual, it democratizes that achievement, as it were. There was a bit of that in our early work too, but that fantasy faded for us after being in the media art community for so long.

Akaiwa: But we’ve been in two minds too about that over our whole career, so I do understand where those engineers are coming from.

In contrast, today’s fine art world still lays strong emphasis on the artist-creator.

Akaiwa: Here in the US, I think you’ll find that even among artists using new media.

Sembo: In that sense, media art offers an antithesis to that kind of “artist-first” culture in a rock-and-roll way. I used to find that exciting, but it changed somewhere along the way. Though I don’t know if it’s media art that changed, or me. Hard to tell at this stage.

Akaiwa: Back when we were regularly going to see live shows at SuperDeluxe in Nishi-Azabu, we did make some work that resembled media art. That was a period when we ourselves were struggling with this very question.

SuperDeluxe played an important role in the Tokyo art scene, didn’t it?

Akaiwa: A lot of our friends belonged to that community, so we used to go almost every day. There’d be something exciting going on whenever we went. And our experiences there were so far removed from media art.

Sembo: Yes, it was lost on many of our friends. [laughs]

Doesn’t media art come in all varieties too?

Sembo: Yes, it’s expanded so much and branched out into so many different directions. I think that what our generation was doing – people like us and Daito [Manabe] – was closer to the sort of thing you see at Ars Electronica. But a growing number of younger media artists are making things that are similar to contemporary art. The boundaries are getting more blurred.

Akaiwa: Another sign that it’s becoming pervasive.

Sembo: Yes, everyone can use a computer now. Where would you go today to find your archetypal media art, I wonder?

Akaiwa: Odaiba, maybe?

That’s a place that leans heavily towards popular entertainment.

Sembo: Media art is getting commercial over here too. You find it used for things like special effects for live concerts. I don’t think there’s that much around yet that can hold its own as art.

A similar thing seems to be happening with movies, which have become so readily available because of services like Netflix. More and more people are watching movies online because of the coronavirus, and some say that this is starting to blur the boundary between commercial and experimental movies.

Akaiwa: Do you mean we’re seeing a rise in experimental movies?

There seems to be more room for experimental work, and more opportunities for independent filmmakers to become involved in Netflix productions.

Akaiwa: That’s great. Looking at Netflix over here in the US, it’s pretty much all popular entertainment – your mind would go numb if you only watched that stuff. It’d be wonderful to throw some experimental things into the mix.

Sembo: Are there experimental filmmakers producing experimental movies on these services?

That might be trickier. But it would be interesting to see what would happen if creators of an experimental bent started influencing commercial movies. Same with media art – hopefully it will encourage more experimentation in the mainstream, rather than just become popular entertainment itself.

Sembo: The platforms have been changing in recent years. I feel as if all art is being slowly reduced to scales dictated by Instagram, YouTube, and so on. It’s almost like you don’t exist if you’re not on those platforms. Realm has its own dedicated website – what they call a “special site.” It used to be quite common to express something through such self-contained websites, including some commercial stuff too. But they’re mostly gone now – they’ve had to change their format to YouTube videos or to 10-second clips on Instagram. I think there’s less variety now as a result.

On the latest work Realm

Could you talk a little about the new work Realmand what that’s about?

Sembo: So New York had gone into lockdown, and the US already had the highest number of coronavirus cases and fatalities in the world. And we would take a walk almost every day in a huge cemetery near our house – Green-Wood Cemetery – where you find all these gravestones in a rich natural environment. It’s an incongruous place where these two totally contrasting elements exist side by side: nature and man-made gravestones. You rarely come across other people there, so it’s safe in terms of the virus too, and you can even see the Manhattan skyline in the distance. Even though the virus had thrown human society into chaos, all the nature at the cemetery remained totally unaffected. We found that very healing in a time like this. In light of this experience, we thought about where we stood as a society – about how we still have limited scientific understanding of the virus, of its modes of transmission, of its precise nature. And we realized just how arrogant humanity has been. These days, we humans like to think we’ve got it figured out, but we’re actually only at a midpoint somewhere along the course of our history and our evolution. That was the sort of thing we were thinking about.

The work also has a technical, web-related element too, something we noted during lockdown as we were preparing artwork for an exhibition that’s yet to be announced. So, in many cases, if you open a URL on a computer web browser, the page that comes up is big and detailed; but if you open the same URL on a smartphone, you get an abridged version of the same page. It was as though, on a smartphone, you’re viewing things more subjectively with a narrower mind, whereas on a browser, you see it more objectively with a broader mind. Even though it’s the same “space,” you’re looking at it in two completely different ways. And we were intrigued by the question of what existed at the midpoint between those two realms, as it were. So, during the lockdown, we started to consider everything in terms of this “midpoint” between realms. We were also feeling like doing some net art again. Recently we’d made a lot of material works, but the lockdown gave us an itch to create works that only exist online. And Realm was the idea that popped up, which neatly connected all these thoughts at their, well, mid-point.

I’d assumed that the notion of the “midpoint” was mainly referring to this current situation of social distancing – I didn’t realize it was also dealing with that interfacing aspect too.

Sembo: Right now, we’re being asked to be sensitive about things we didn’t worry about before, like minimizing contact to avoid infection. But we still touch our smartphones all the time. So we made a mechanism that shows up fingerprints when viewers touch the screen, which serves as a reminder of the presence of this membranous screen that we’re constantly touching. The page on the smartphone, an object that’s very tactile and very close to us, has been made interactive, while the web browser version is totally out of our control. And the work interrogates through that dual structure what lies at the midpoint between the two sides.

In terms of medium, Realm is also a photographic work, and the web browser version shows a slideshow of photos that get closer and closer to the graves. You have that photography, which is a medium that offers no interactivity, but you’re also able to touch the images on smartphones. So there’s also this idea of the midpoint between interactive artwork and static photography.

The work gets a real reaction out of people when they first view it on their smartphones. And I think it’s regular people who react more strongly. The beautiful photographs also make it more accessible.

Sembo: We began working on Realm early on in the lockdown, and so there’s a sense of the vulnerable feeling that we had back then. But we like how the work turned out – I think it expresses our current state quite accurately, in a poetic but plainspoken sort of way. And the “words” comprising that poem are digital devices, such as smartphones, and their interrelationship.

This is something I only just noticed, but I guess Realm is also a fusion of two other opposing elements: a classical medium like photography, which we’d rejected as youths, and interactive media art, which turned from a fantasy into reality. Our present challenge is to find a way to make such contradictory elements coexist.

(Conducted over video chat on the night of June 13[New York]/morning of June 14[Tokyo], 2020; interviewed/edited by Tasaka Hiroko, Curator of Tokyo Photographic Art Museum)